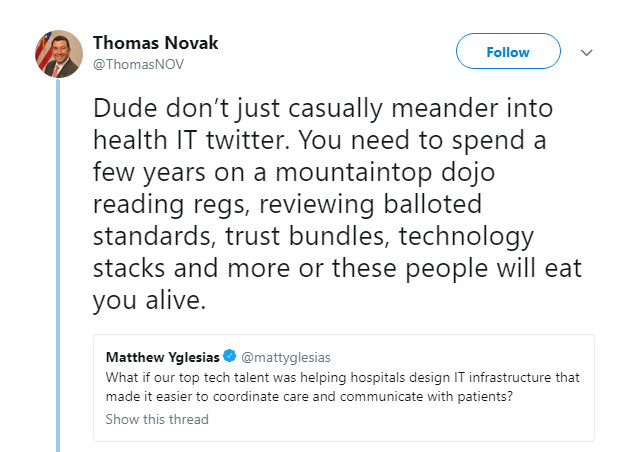

For those who haven't been in a mountaintop dojo reading Health IT regulations the last few years (see tweet above or here), I'm happy to share that patient health data is now available to authorized parties about as conveniently as you can order a latte using the Starbucks app. (Maybe even more so, since you don’t even have to pick up the health data in person.)

Thanks to the technologists who have already done this reading—and then some—patients won’t need to do any of the heavy lifting referenced in this tweet in order to take advantage of emerging health data liquidity. Healthcare organizations whose software is certified under the latest and greatest edition of ONC base requirements now offer, or will soon offer, self-service APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) that are beginning to disrupt healthcare delivery as we know it. For just about all providers except those who are excluded or don’t mind suffering reimbursement penalties, APIs are beginning to be rolled out at scale this year.

This move is a first step toward less time spent waiting for busy healthcare providers to respond to your personal health data RFI (also known as an Individual Right of Access request). Plus, instead of getting a fax or a credential you can use for admission only to the provider’s patient portal, you’ll now also receive or can look up a sort-of bookmark that you can use to access your health data with any application you choose. A collection of all such bookmarks available for a single person constitutes a good part of that person’s complete longitudinal health record (minus records from providers who don't offer APIs…which is hopefully very few). Whether accessing one’s own data, or someone else’s records if authorized, health data can now be managed much like the way access to information is controlled in applications such as Google Docs.

What’s disruptive about this? APIs separate the data and how it is secured from the software being used to view that data. In almost the same way a web site can be viewed using a variety of different browsers. This allows health data to be used in custom applications and simply makes it more shareable, while still being subject to the same security and privacy rules. Patients can then do more with their health data, correcting errors, preventing repeated tests, and managing its collaborative use across their care teams like never before. This disruption will be life-changing, quite literally.

What’s interesting about APIs is that a lot of disruption has already taken place. So, although telemedicine, artificial intelligence, and customer relationship management advancements may leverage APIs to dramatically improve care delivery in the coming years, it won’t take any heavy lifting by Amazon or Google or Apple to enable that progress. True disruption began when the U.S. Government started chipping away near the top of the health data “mountain” a few years ago, publishing the 2015 Edition meaningful use regulations. The timing of this coincided with FHIR's increasing maturity as a solution that could be used to meet the Open API requirements in those regulations. Another step in patient data independence was the API Task Force declaring that patients should be able to choose their own apps. The beauty in this modernization is that every provider is enabling the disruption themselves by turning on these services and doing their part in this great health information liquidity “avalanche”.

Warning: increased efficiency up ahead!

But the true power of this capability will be in the way it scales, because even APIs will still be a lot of work to use, if signing in to one instance of my health data still means signing in to Only. One. Instance. of my health data, having to use a different application or patient portal each time.

Instead of doing that, assembling your health data from different provider organizations will soon be as effortless as shopping online from multiple different web stores, using a single PayPal login. Or like checking for messages from several different email accounts through a single email client. And there won’t be just one website or software application that gives you this flexibility—you can pick the one that’s been suggested by your physician’s practice, or the one that gets a nod from all your nerdy, security-savvy friends. The important takeaway is that an environment ripe for curing “portalitis” once and for all has been established, and it will empower patients with appropriately-modern personal health dashboards, where they can access records from their providers’ various systems all in one place if they choose.

APIs enable the experience of something like “Mint for Healthcare” without having to do all the screen scraping Mint does to make that magic happen, and potentially without the need for one-off legal agreements between every pair of different systems. Apple and any other client application can serve as a one-stop-shop for your health data without necessarily having to execute a new contract between every client application and every provider organization that makes data available through an API. Using their own credentials, patients can bookmark every one of their providers’ APIs in a single app and have all their digital health data accessible from within that one application.

It’s really great to see companies like Apple building apps that can leverage APIs. The iOS Health app definitely helps to generate awareness about patient access to data—and not just for the iPhone owners who use it. (For now, at least, Apple's Health app is not available on the iPad.) What's newsworthy is not so much the number of new additional healthcare systems available in Apple Health each week, or that they've enabled a basic FHIR browser app, but that this work is being done by Apple, who emanates a special kind of geek chic. Browsing one's health data is now a thing.

So, what's next after this well-publicized Beta? Will Apple connect to every rural hospital's data? Every small provider? Skilled nursing facilities? Chiropractors? EMR vendors who implemented proprietary APIs instead of FHIR? Is there an 80/20 rule here?

And will patients like having the option to access health data from their phone or other device (via Apple Health or a different FHIR client)?

Fortunately, we are well on our way to finding out!

---------

Julie Maas is founder and CEO of EMR Direct, developer of the Interoperability Engine API management platform which includes Direct Messaging, HL7 FHIR®, and identity services; and of the HealthToGo® patient portal and FHIR client application. EMR Direct provides interoperability services to thousands of healthcare organizations nationwide and specializes in simplifying the level of effort required for developers to enable these services within their applications.